We’ve discussed how much debt is floating around out there. America’s bar tab was around $54 trillion; half of that was money owed by the federal government, and a quarter of it was credit cards, auto loans, mortgages, and other instances of consumer debt. While a smidge of the rest of it consisted of the obligations of states, cities, and other non-federal borrowers in the public sector, corporate bonds accounted for around $10 trillion in red ink.

It’s fair to ask: How risky is it to buy the liabilities of American corporations?

Warning track

As we have said before, debt itself isn’t a bad thing. It is generally a cheaper source of capital than issuing more stock, so companies like to do it. If an auto parts company can borrow money at 5% to build a factory that will allow it to sell products with a profit margin of 10%, it’s a no-brainer.

But there is such a thing as too much debt. The more corporate bond debt a company has in proportion to its equity, the less leveraged it is, and thus the stronger a position it’s in to weather a downturn. In aggregate, the S&P 500’s debt-to-equity ratio was 1.6 at the end of last year, according to Forbes, and that was considered healthy. That meant its liabilities were worth 60% more than what they owned free and clear, so don’t try this at home.

This is not a one-size-fits-all number; some industries are more capital-intensive than others, so they’re bound to need more debt financing. You know, like airlines. According to Investopedia, that industry’s benchmark debt-to-equity ratio is a couple of orders of magnitude higher. It was 115.6 before the world went sideways and has likely only gone higher since.

Also, the debt-to-equity ratio’s numerator is total debt, not just long-term bonds. That means one company that just ran up its credit card to acquire inventory it expects to sell before Christmas or another that borrowed some short-term cash to buy out a competitor in a clearly accretive deal will have temporary leverage issues which shouldn’t affect their overall credit rating.

Even so, if there’s no money coming in the door, these nuances are moot.

“As corporate borrowers confront both operating constraints due to social distancing and diminished consumer demand, the recovery path will likely be rocky and uneven, and many in the industries hit hardest by the severe economic shock will be lucky to escape default,” writes S&P Global credit analyst David C. Tesher. “[C]orporate borrowers have incurred more debt, and concerns about high leverage and potential for insolvency are increasing.”

And yet, there is no shortage of lenders.

“[F]inancing conditions for U.S. corporations have improved … faster than economic data have,” Tesher continues. “Equity and fixed-income markets are showing exceptional optimism even as new cases of the virus have risen in some areas and the full reopening of the economy is some way off.”

If this reminds you of all those mortgage lenders who were burning up the phone lines in 2008, then you’ve been paying attention.

Asking no questions

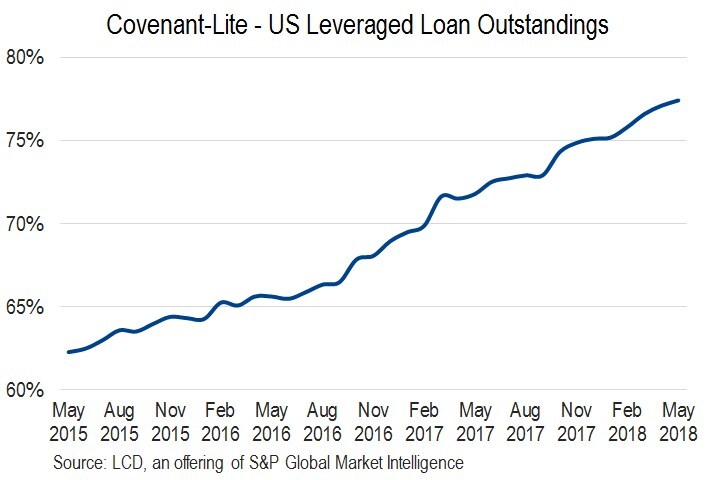

So-called covenant-lite lending–in which terms are light on restrictions related to performance, cash flow or collateral–was flourishing even before the outbreak, and it is absolutely in full bloom now. So don’t be confused if you see a reference to a “cov-lite” loan; in this case, “cov” is short for covenant, not coronavirus. But the results could still be devastating. And similarly, there are plenty of people who think that the risk of exposure to cov-lite loans is entirely overblown.

Still, we seem to be in the middle of a cov-lite pandemic. According to Global Finance, 17% of loans in 2007 were predicated on cov-lite terms; by 2018, it was as much as 80%. As companies continue to face cash flow issues, they might tend to seek these out even more so.

“This crisis is a real test case for covenant-lite. If credits recover, then sponsors will emphasize the necessity of such flexibility,” Edward Eyerman, head of leveraged finance at Fitch Ratings, told Reuters. “In contrast, if recovery does not develop meaningfully then we will have fully drawn defaulting and zombie credits.”

And if there’s something we don’t want to see during a viral outbreak, it’s zombies.

But, while a company can take out all the cov-lite loans it wants, it still has to face the bond markets eventually, and that means passing muster with the credit rating agencies. That’s going about as well as you’d expect.

While there has been a worldwide increase in exposure to potential bond defaults, “changes in risk metrics during the pandemic period point squarely to the United States as the single highest credit risk concern,” according to a globally scoped Moody’s Analytics report.

You already own it

That means companies are facing downgrades to their bond ratings. The Federal Reserve has gone ahead with the unprecedented step of buying high-yield bonds. They’re often called junk corporate bonds, but that’s probably more denigrating a title than they deserve. They generally do get paid back but are riskier than so-called investment-grade bonds.

To use Standard & Poor’s methodology for the sake of consistency, an investment-grade bond is rated BBB or better, and what they prefer to call “non-investment grade” or “speculative grade” bonds are rated BB or lower.

Why is it important to know about junk corporate bonds? Because, thanks to the Fed, you own these non-investment grade bonds. While the monetary authority’s usual open-market operations involve buying and selling U.S. Treasury obligations, it is now buying high-yield corporate securities. Although to qualify for the program a company’s bonds had to be rated investment grade on or before March 22 before sinking below the line during the shutdown. Investopedia reports there are almost 800 of those, but they might not have to wait in line too long. America’s central bank has an announced $750 billion appetite for high-yield corporate bonds.

Don’t be a zombie investor

We mentioned in May that we weren’t sold on the legality of this action, but it does appear to be going forward. And if you squint hard enough you might even be able to see that as a good thing. The Fed’s action could stem the tide of corporate bankruptcies, which have spiked by 26% this year, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Of course, there are the typical moral hazard arguments. But the fact that, in 2008 and 2009, we decided not to send any bankers to jail, then allowed the “too-big-to-fail” banks to get even bigger so they can mess up even worse and not fail, means those old platitudes about thrift and personal responsibility fall on deaf ears.

But now the public sector is in effect lending speculatively to private companies. Yes, that’s the result of the Fed’s recent actions, but it’s also a cornerstone of the CARES Act.

It comes down to people not having money, so people aren’t spending money, so companies are being caught short on their obligations, so their cost of borrowing is going up, so the possibility they’ll default keeps going up, so Washington is trying anything it can think of to stave off a rash of bankruptcies. That said, there’s a lot to unpack there, so maybe it’s best to consult a financial professional.

Meantime, if you see a zombie, just run. Don’t ask it for its credit score.